Every child has the right to survive and thrive.

About the Global

Network of Religions

for Children

The Global Network of Religions for Children (GNRC) is a global interfaith network of organizations and individuals dedicated to securing the rights and well-being of children everywhere.

The Impact of the Network

56M faith leaders, adults, and children

What leaders are saying about GNRC

Our work in 73 countries

Every child has the right to survive

-ql8wxl2hk5xatx69xe6abvwh7pd2g4sl3ibgqwku40.jpg)

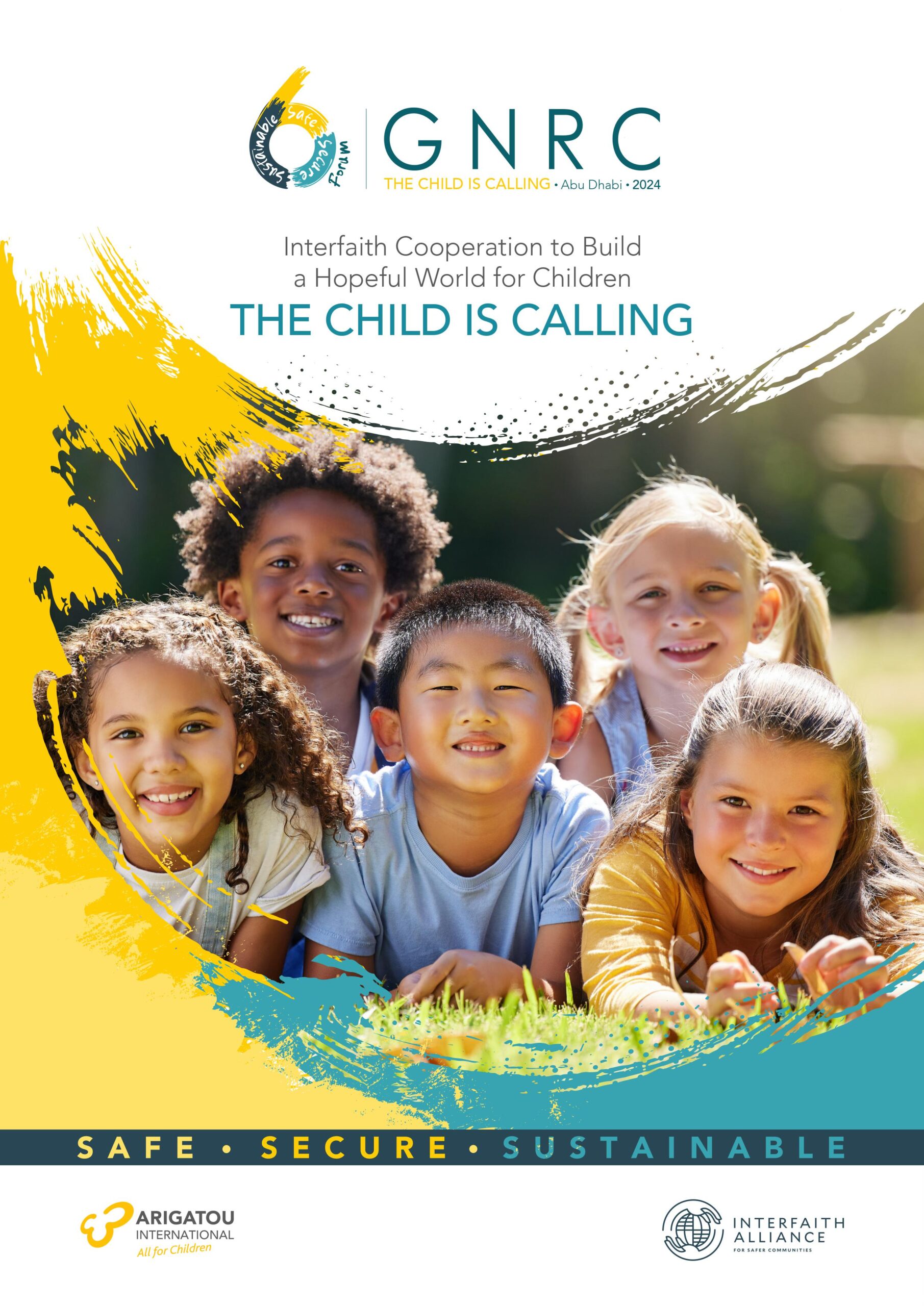

Announcement of the GNRC Sixth Forum

On behalf of Arigatou International and the Global Network of Religions for Children (GNRC), I am pleased to announce that the GNRC Sixth Forum will be convened from November 19 – 21, 2024 in Abu Dhabi, UAE. The Forum will be hosted by our partners, the Interfaith Alliance for Safer Communities.

The GNRC was inaugurated in 2000 by my father, the late Rev. Takeyasu Miyamoto, out of his strong conviction that it is the moral responsibility of people of all faiths to protect the lives of children and ensure their safe and sound development. He proposed that people of every faith and religion join hands and work together, regardless of differences, to build a better world for children.

Keishi Miyamoto (Rev), President of Arigatou International, Convenor of the Global Network of Religions for Children

Hope for Children in a World in Crisis

Over the last six years, GNRC members and partners worldwide have worked tirelessly to fulfil the 2017 GNRC Fifth Forum 10 Panama Commitments on Ending Violence Against Children.

Thousands of children have had their lives transformed at the grassroots level by the efforts of hundreds of GNRC members across 75 countries.

Even as this transformation takes place, new challenges have emerged. Not since World War II has there been a time like today, when so many children are directly targeted for harm, or caught in harm’s way.

The statistics are horrifying and deeply distressing.

Mustafa Y. Ali (PhD) Secretary General of the Global Network of Religions for Children (GNRC) Director, Arigatou International – Nairobi

Panama Commitments

The Panama Declaration on Ending Violence Against Children

GNRC Around the World

We invite GNRC coordinators and contact persons to apply funds for GNRC activities that promote networking for interfaith harmony, understanding, and cooperation to build a better world for children.

What We Are Reading

Faith and Children’s Rights: A Multi-Religious Study on the Convention on the Rights of the Child

We invite you all to read this comprehensive study of the Faith and Children’s Rights.